A fragile confession where a once powerful voice pauses to ask for understanding rather than applause

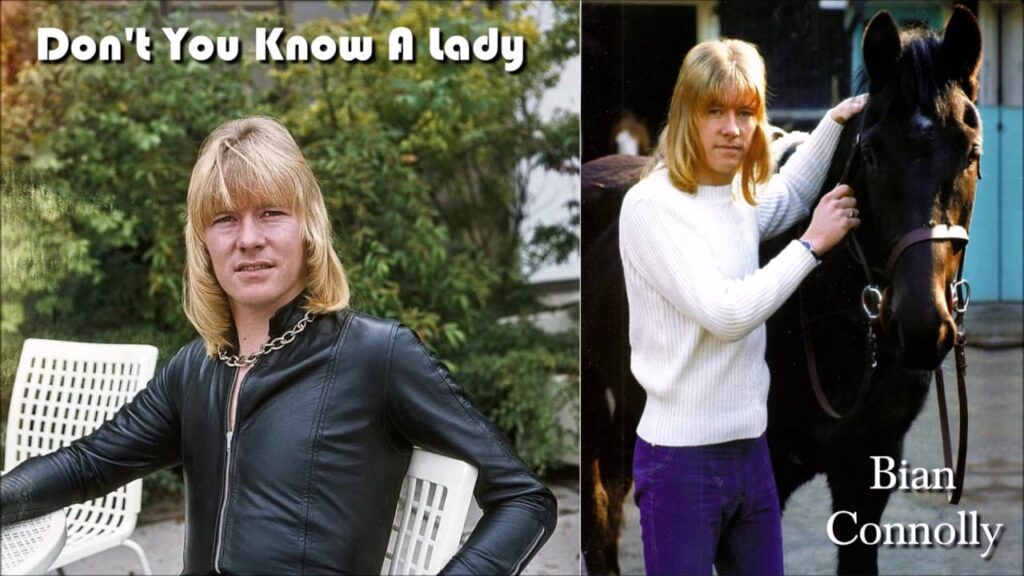

When Brian Connolly released Don’t You Know a Lady in 1978, it was not simply a new single entering the marketplace. It was a moment of exposure. For many listeners, this song marked the first time they encountered Connolly not as the flamboyant, sharp suited frontman of Sweet, but as a solitary voice carrying weariness, longing, and a quiet plea for recognition beyond fame.

Issued as his debut solo single on RAK Records, Don’t You Know a Lady reached No. 34 on the UK Singles Chart in the summer of 1978. While modest compared to the towering chart dominance Sweet had enjoyed earlier in the decade, the placement was significant. It signaled both continuity and rupture. Connolly was still present, still heard, but standing alone in a musical landscape that had changed, and in a personal life that had been profoundly reshaped.

By the late 1970s, Brian Connolly had already lived several musical lifetimes. As the unmistakable lead voice on hits like Ballroom Blitz, Fox on the Run, and Love Is Like Oxygen, he embodied glam rock’s theatrical confidence and melodic precision. Yet behind the bright colors and arena choruses lay years of strain, illness, and internal fractures within the band. His departure from Sweet in 1977 was not triumphant. It was quiet, complicated, and deeply human.

Don’t You Know a Lady reflects that emotional terrain with surprising directness. Written by Mike Chapman and Nicky Chinn, the same legendary songwriting duo behind many of Sweet’s biggest successes, the song feels deliberately intimate. It carries none of the bombast of glam rock. Instead, it leans toward a polished, late seventies pop ballad style, guided by tenderness rather than spectacle.

Connolly’s vocal performance is the heart of the recording. His voice, once razor sharp and commanding, now sounds softer, occasionally strained, but profoundly sincere. Rather than hiding those imperfections, the song allows them to remain. They become part of the story. There is vulnerability in the way he phrases each line, as if the song itself might slip away if held too tightly.

Lyrically, Don’t You Know a Lady is about misunderstanding and emotional distance. The narrator speaks to a woman who has perhaps judged too quickly, asking for patience, for deeper seeing. It is not a demand. It is a request. The repeated question in the title carries more ache than accusation. It suggests a man aware of his flaws, yet still hopeful that he might be understood beyond them.

In retrospect, the song’s meaning extends far beyond romantic context. It reads almost as a broader reflection on Connolly’s own position at the time. A singer once celebrated now standing outside the machinery of a successful band, asking the world to look again, to listen differently. There is dignity in that ask, even when it goes unanswered.

The production remains tasteful and restrained, characteristic of RAK Records’ late seventies sound. Strings and soft rhythm support the melody without overwhelming it. Everything is designed to keep focus on the voice and the sentiment. This choice feels intentional, as though the song understands that its strength lies in emotional clarity rather than innovation.

Although Don’t You Know a Lady did not restore Brian Connolly to the commercial heights of his earlier career, it achieved something quieter and arguably more lasting. It revealed an artist willing to stand without armor. In doing so, it offered a different kind of connection, one built not on excitement but on recognition.

Today, listening to Don’t You Know a Lady feels like revisiting a crossroads. It captures a moment when fame has already passed its peak, but the need to be heard remains undiminished. Brian Connolly sings not as a symbol of an era, but as a man navigating change, loss, and hope with what voice he has left.

That honesty gives the song its enduring resonance. It may not shout for attention, but it stays with you, lingering like a question asked softly, and remembered long after the music fades.