A quiet tableau of lost love in a café, marked by three cigarettes in an ashtray

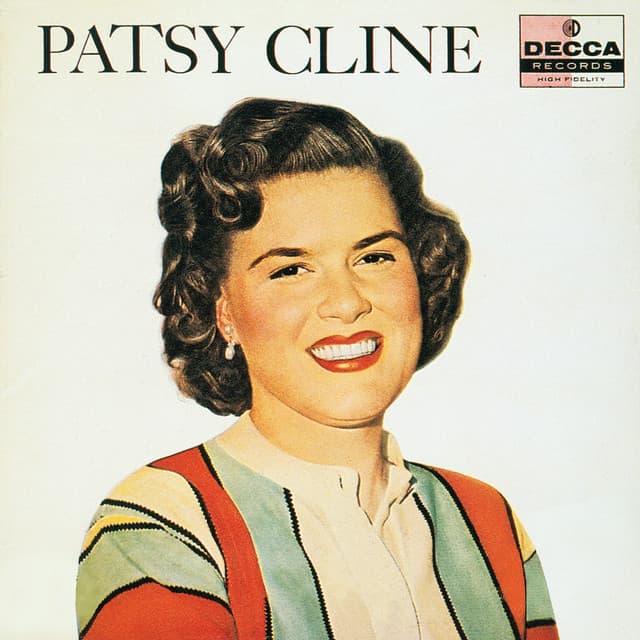

By the time Three Cigarettes (in an Ashtray) found its way into the world on August 12, 1957, the voice of Patsy Cline was already pressed into memory by her breakout hit Walkin’ After Midnight. Despite the artistry at hand, “Three Cigarettes” did not chart in the major rankings at the time of its release. Yet the lack of immediate commercial success in no way diminishes the emotional weight and craft that Cline brought to the performance. The single was issued by Decca Records (leased via her Four Star arrangement) with the B‑side A Stranger in My Arms, and it was included on her self‑titled debut album Patsy Cline later that year.

The story behind the song may not be bound to a singular documented incident, but its conception and recording carry a distinct imprint of longing and quiet heartbreak. Penned by songwriters Eddie Miller and W.S. Stevenson (the latter a pseudonym of Four Star executive Bill McCall), the song was tracked on April 25, 1957, in New York at Decca’s studio with The Anita Kerr Singers accompanying Cline. It arrives at a moment when Cline was expanding beyond her early country‐honed sound into a pop‑tinged palette, but never losing the loner’s heart of her musical identity.

From the first line—“Two cigarettes in an ashtray / My love and I in a small café”—the scene is set in miniature, intimate and sorrow‑tinged. The arrival of a third cigarette, as the lyric continues, signifies the presence of a stranger, the intrusion of a new love, and the departure of the subject’s own: “Then a stranger came along / And everything went wrong / Now there’s three cigarettes in the ashtray.” That simple image—the ashtray as witness—carries more emotional freight than any grand scandal. To watch one’s partner drawn away, leaving you to smoke the final cigarette alone, is to experience the subtle cruelty of absence more than the eruption of betrayal. Cline delivers this with crystalline poignancy: the low hum of the arrangement, the slight quiver in her voice, the space between the notes all contribute to the sense of a person suspended in a moment of loss.

Musically, the track is lean and evocative. Clocked at approximately 112 BPM and set in a moderately paced meter, the song opts for economy: no frills, no ornamental excess. ( The backing harmonies of the Anita Kerr Singers and the subtle steel and guitar flourishes serve as atmospheric coloration rather than dominating elements. It is as though the instrumentation knows its place—to bolster the mood, not overshadow the story. In the larger arc of Cline’s career, this is significant: after the commercial success of “Walkin’ After Midnight”, there was pressure to replicate that crossover appeal, but with “Three Cigarettes” she remains tethered to melancholy realism rather than chase pop gloss.

Though the single did not chart, over time it secured a place among Cline’s essential recordings. Critics such as Stephen Thomas Erlewine have named it an “album pick” and pointed to it as evidence that even her less‑commercial outings contained “essential listening.”The fact that it was included in later compilations—such as the 1998 The Ultimate Collection—speaks to its enduring resonance.

For the listener steeped in time—those who remember the crackle of vinyl, the hush that falls when the room darkens and only the needle’s whisper remains—“Three Cigarettes (in an Ashtray)” can feel like a photograph scratched with ache. It is not about dramatic heartbreak; it is about the small, precise moment when love asks one of its participants to step aside, and the world carries on—with or without them. The ashtray, the cigarettes, the café—they are props in a quiet theatre of departure. Cline does not beg or rage. She simply observes: “And I sit alone and watch one cigarette burn away.” The extinguishing cigarette becomes a metaphor not only of a relationship’s demise, but of a self becoming unlit in the glow of someone else’s flame.

In reflecting on this song now, one recognizes how Cline devoted her artistry to framing the everyday with lyric and sound. The charm of “Three Cigarettes” lies in its understatement: a café, two cigarettes, a stranger, a departure. No loud declarations, no sweeping serenades. Just the shift of presence, captured in three glowing but fading embers. And in that simplicity, the song becomes timeless. It whispers that we all have sat alone with our unlit match, our cigarette half‑smoked, watching someone else’s story unfold while our own remains ash. In her voice, that universal regret becomes beautiful and enduring.