Under the Shadow of the Cottonwood: A Ballad of Fate and the Quick Draw

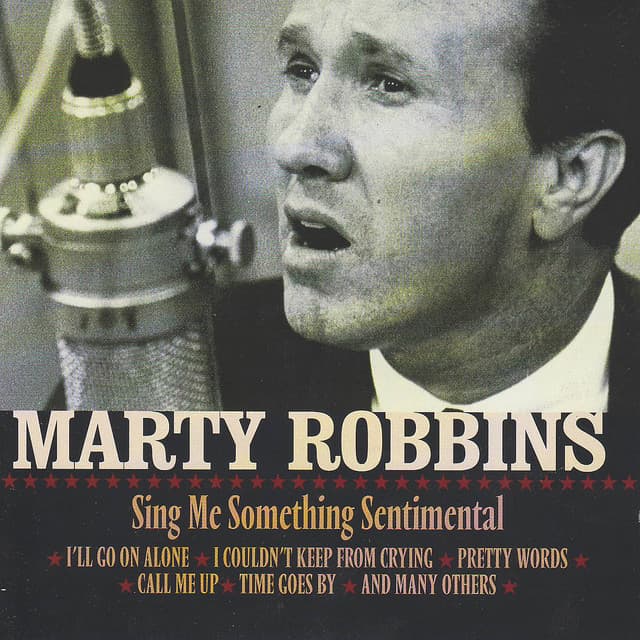

There are certain songs that, the moment the first mournful acoustic guitar notes drift out of the speaker, transport you back to a specific, almost mythical America—a land of arid dust, hard men, and even harder justice. Marty Robbins, a true master of the genre, gave us many such musical Westerns, but few carry the heavy, fatalistic weight of “Cottonwood Tree.” Released in 1966, this track serves as a chilling, first-person epitaph, a final lament from a man standing at the very edge of life.

A standout not as a major hit single, but as a deep cut that defines the latter half of his ‘Gunfighter Ballads’ style, “Cottonwood Tree” was a grim entry into the canon of storytelling songs that Marty Robbins so brilliantly popularized. Unlike the crossover chart success of earlier epics like “El Paso” (a phenomenal Billboard Hot 100 and Country No. 1), “Cottonwood Tree” did not achieve a high chart position, or in some regions, any chart recognition at all. It was the kind of song that old-school country and western fans sought out, the perfect complement to albums like Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs, even if it wasn’t on that specific 1959 masterpiece. The song’s power lies not in its popularity, but in its dark, unflinching narrative honesty, a testament to Robbins‘ commitment to the Western tale.

The story itself is a quick and brutal lesson in frontier irony. The narrator, a cowboy just riding into Tucson for supplies, gets into a friendly poker game at The Miner’s Saloon. Lady luck seems to smile on him, doubling his stake, only for fate to reveal its cruel hand. A young cowboy he beat at the table accuses him of cheating, draws his gun, and is shot down in self-defense. The narrator, believing justice will prevail, hands his gun to the Sheriff. The immediate crowd turns ugly when it is revealed that the dead boy was the town’s most influential man’s only son. His claims of self-defense are ignored by the furious, grieving townspeople, who quickly drag him out to the hanging spot—a solitary, majestic “Cottonwood Tree.”

The sheer helplessness of the narrator, who did “no wrong” but must now “with my life… pay,” is what makes the song so heartbreakingly real. The lyrics are pure, unvarnished poetry of doom, painting the final scene with strokes of terrible clarity: his old horse, Dan, is beneath him, a noose is around his neck, and the bereaved father takes a branch from the tree to whip the pony out from under his son’s killer. It is a terrifying, vivid vision of mob justice prevailing over due process.

When we hear this track now, it’s a nostalgic reminder of the pure narrative genius of Marty Robbins. He was more than a singer; he was a troubadour of the dusty trail, an aural novelist whose voice could transform three minutes of music into a fully realized Western movie. His gentle baritone, usually so smooth and comforting, takes on a resigned tremor here, evoking the final, desperate plea of a man looking up at a “sky’s growing dark overhead.” For older readers who remember the golden age of the Western genre, whether on the silver screen or the radio, “Cottonwood Tree” is an emotional link back to a time when a story, well told and sung, was the highest form of entertainment. It serves as a stark reminder that in the Old West, fate often hung as heavy and inevitable as the gallows rope.