Marty Robbins – Running Gun: The Tragic Testament to a Life Forfeit for the Love of the Draw

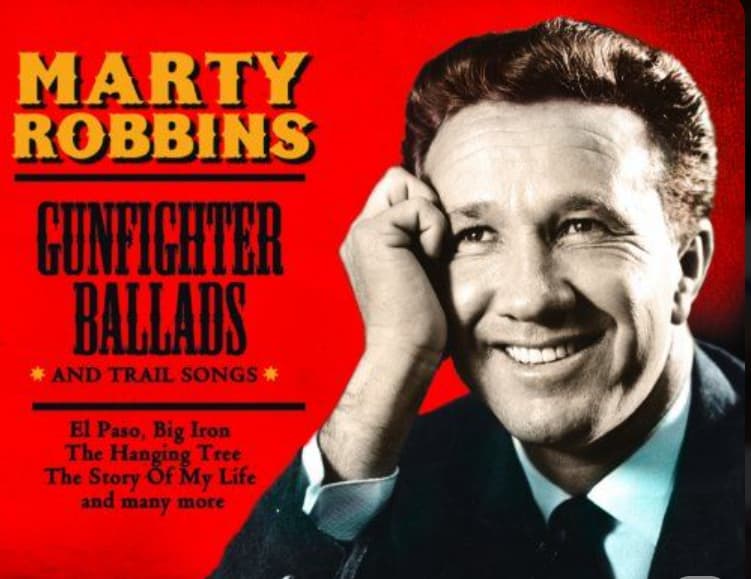

To revisit the seminal Marty Robbins album, Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs, is to step into a world of dusty trails, high stakes, and the timeless moral code of the Old West. Released in 1959, this record is perhaps the greatest single collection of narrative Western songs ever produced, and while the majestic “El Paso” rightly claimed the spotlight, the B-side to that chart-topping single, “Running Gun,” provides a poignant, necessary counterpoint—a short, sharp dose of tragedy that perfectly complements the epic romance.

“Running Gun,” penned by the talented Glaser Brothers, Tompall and Jim Glaser, was released in late 1959 as the flip side to Marty Robbins’ eventual crossover smash, “El Paso.” While the A-side famously topped both the Billboard Hot Country Songs and Billboard Hot 100 charts, “Running Gun” did not chart independently. Its primary significance on the charts is its enduring connection to “El Paso,” riding the coattails of the hit to become one of the most recognized B-sides in country music history. Its presence cemented the album’s theme, ensuring that every song, even the shortest one, contributed to the overall mythological atmosphere.

The story behind “Running Gun” is a classic Western tragedy: a man realizing too late the profound cost of the life he has chosen. The narrator is a “gun-for-hire outlaw” with “twenty notches on [his] six gun,” a life earned by selling his speed for a few dollars. Unlike the romantic impulse that drives the hero of “El Paso,” this man is driven by guilt and a yearning for a future that his bloody past has already precluded.

The lyrics reveal his desperate attempt at redemption: he leaves his love, Jeannie, in Kansas City with a promise to send for her once he reaches the safety of Old Mexico. He rides into Amarillo, exhausted but hopeful, only to be ambushed.

“I had barely left the saddle, and my foot just touched the ground When a cold voice from the shadows told me not to turn around”

The ambush—quick and decisive—is the reality that often undercuts the romantic mythology of the gunfight. He is challenged by a ruthless bounty hunter, and though he attempts to draw, he is simply not fast enough. It is an honest, brutal depiction of the unforgiving nature of the gunfighter’s fate: “My own gun stood in leather as his bullet tore its path.”

The meaning of the song crystallizes in the outlaw’s dying thoughts. As his life fades, his final words are not of vengeance, but of regret for the love he has tainted and lost. He asks the bounty hunter to relay a message to Jeannie, one of heart-wrenching remorse:

“Oh, please tell her won’t you, mister, that she’s still the only one But a woman’s love is wasted when she loves a running gun.”

This final, fatalistic line is the emotional weight of the song. It’s a profound meditation on the incompatibility of a life of violence and a life of domestic peace. For the seasoned listener, especially those of us who came of age during the era of classic Westerns and country story-songs, “Running Gun” is a poignant reminder that while a fast draw might earn a man money or infamy, it will always cost him his chance at a tranquil, lasting love. It’s a testament to the artistry of Marty Robbins and his collaborators who, in just over two minutes, could craft a tragic narrative as memorable as any hour-long picture show. It’s the short, sad ballad of a life spent running, only to be caught at the last turn.