A familiar hymn, sung softly enough to feel like a prayer remembered rather than a performance

When Anne Murray released her rendition of “Amazing Grace” in 1999 as part of the album What a Wonderful World, it was not aimed at radio dominance or chart competition. The recording was not issued as a commercial single and therefore did not enter the major pop or adult contemporary charts at the time of release. That absence from the rankings is, in many ways, part of its meaning. This version of “Amazing Grace” arrived quietly, intended less to be measured by numbers than to be lived with, returned to, and trusted in moments when music becomes a form of shelter.

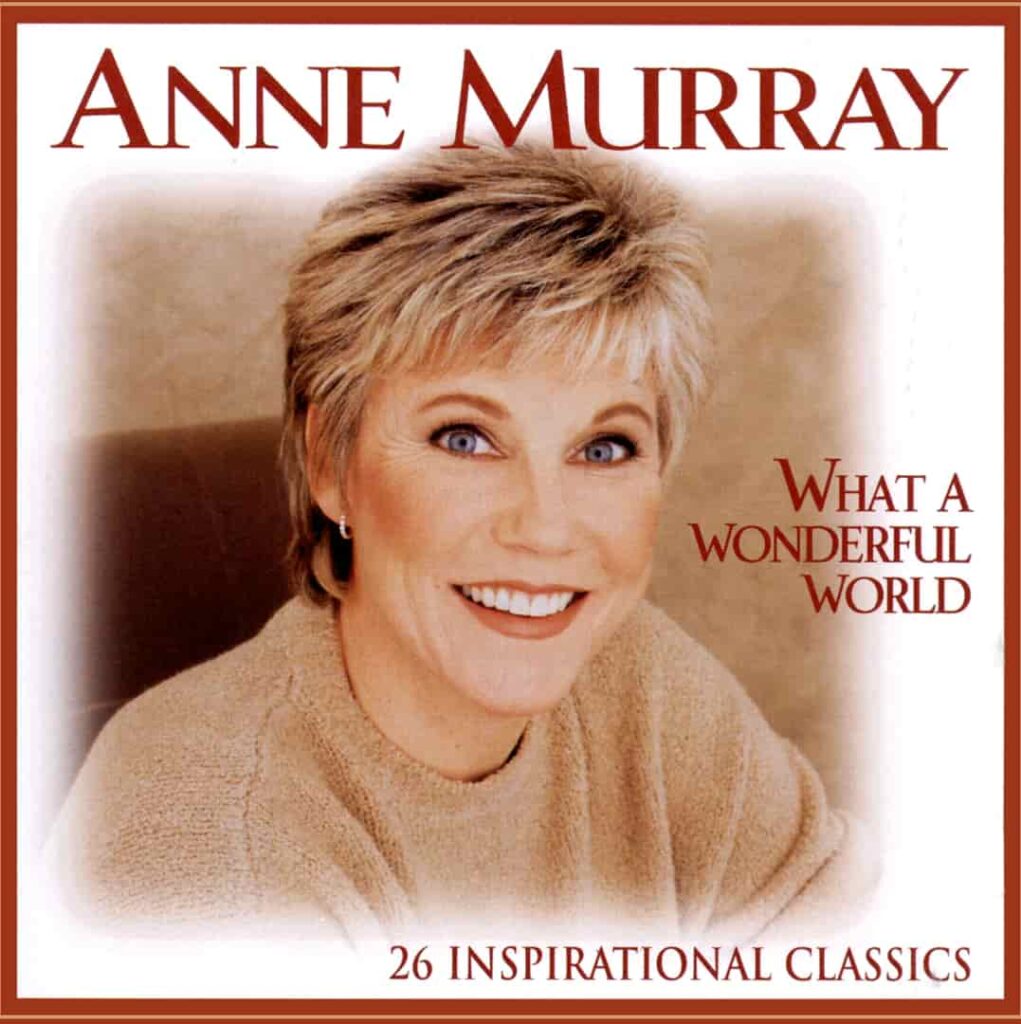

By 1999, Anne Murray was already a deeply established voice. She had crossed decades with grace of her own, earning four Grammy Awards, countless Juno Awards, and a reputation for calm emotional authority. Her career had been built not on vocal excess, but on restraint. That restraint is exactly what defines her interpretation of “Amazing Grace.” Recorded for What a Wonderful World, an album devoted to traditional songs, hymns, and standards, the performance reflects an artist looking backward with gratitude rather than forward with ambition.

“Amazing Grace” itself carries a history few songs can rival. Written in the late eighteenth century by John Newton, a former slave trader turned Anglican clergyman, the hymn is inseparable from themes of repentance, redemption, and moral awakening. It has been sung at funerals, civil rights gatherings, church services, and private moments of grief and hope. Any artist approaching it must decide whether to interpret or simply to serve. Anne Murray chooses service.

Her voice here is unmistakably her own. That warm alto, slightly husky, unfailingly steady, enters without flourish. There is no dramatic build, no climactic reach for emotional effect. Instead, the phrasing feels conversational, almost confessional. Each line is delivered as if it has been lived with for years. This is not the voice of someone discovering faith, but of someone who has walked alongside it long enough to understand silence as part of belief.

The arrangement reinforces that sense of stillness. The instrumentation is sparse and respectful, allowing space between phrases. There is room to breathe, to remember, to reflect. Nothing crowds the melody. Nothing competes with the words. In an era when many gospel and inspirational recordings leaned toward grand orchestration or vocal theatrics, this restraint feels deliberate and deeply considered.

Within the context of What a Wonderful World, “Amazing Grace” serves as a spiritual anchor. The album as a whole reflects Murray’s long-standing affection for songs that endure beyond trends. It was released late in her recording career, at a time when her artistic identity was fully formed and free from external pressure. That freedom is audible. She does not sing to persuade. She sings to reassure.

What makes this recording particularly resonant is its emotional posture. There is humility here, but also certainty. The famous line “was blind, but now I see” is not dramatized. It is accepted. Sung plainly, it carries the weight of a life that has known disappointment, endurance, and quiet triumph. For listeners who have gathered their own years and memories, that plainness speaks louder than any embellishment.

This version of “Amazing Grace” does not ask to be admired. It asks to be trusted. It feels suited to early mornings, to evenings when the world grows quieter, to moments when one is less interested in being moved than in being steadied. Anne Murray understood that some songs are not meant to be interpreted anew, but to be held gently, passed along without fingerprints.

In the end, her recording stands as an example of mature artistry. It reminds us that music does not always need to reach outward. Sometimes it turns inward, carrying with it the accumulated calm of experience. In that sense, Anne Murray’s “Amazing Grace” is less a performance than a companion, one that remains, patient and unassuming, long after the final note fades.