A Timeless Trail Ballad: The Haunting Innocence of a Lost Cowboy

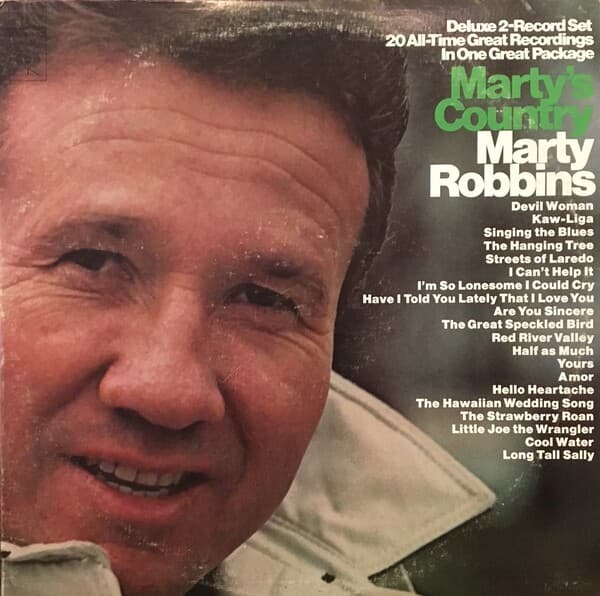

There are certain songs that carry the dust of the trail and the weight of a life lived hard and fast, and few do it with the poignant power of “Little Joe the Wrangler.” When Marty Robbins, the quintessential balladeer of the American West, recorded his version, he didn’t just sing a song; he breathed new life into an enduring piece of folklore. This classic cowboy lament was released in July 1960 on the album More Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs, the essential follow-up to his massively successful 1959 masterpiece. While the album itself was a commercial success, lauded by country disc jockeys and cementing Marty Robbins’ status as the genre’s premier storyteller, “Little Joe the Wrangler” was a traditional song and did not register as a charting single itself, instead existing as an integral part of the album’s sweeping Western narrative tapestry.

The story behind the song stretches back much further than Robbins’ 1960 recording. “Little Joe the Wrangler” is a genuine American folk song, originally written in 1898 by N. Howard “Jack” Thorp while on a cattle drive from New Mexico to Texas. Thorp, a Harvard-educated man who immersed himself in the cowboy life, later included it in his 1908 volume, Songs of the Cowboys, the first collection of its kind. Its melody was borrowed from the older tune, “Little Old Log Cabin in the Lane,” a testament to how folk music evolves and travels across the land.

The meaning of “Little Joe the Wrangler” is heartbreakingly clear and deeply resonant, especially for a generation that grew up cherishing tales of grit and the unsparing nature of life on the frontier. It tells the saga of a small, solitary runaway who rides into a cow camp on a meager pony, looking for work after escaping an unhappy home. Though the crew leader notes the boy’s rough appearance—his “brogan shoes and overalls”—he sees the essential good in the “little Texas stray” and kindly takes him in, assigning him the job of horse wrangler. Joe learns quickly, becoming a valued member of the outfit, yet the rough hand of fate is swift and unforgiving. During a sudden, violent “norther” (a rapid cold front) that causes a massive cattle stampede, Little Joe is called to ride guard. In a flash of lightning, the cowboys see the little figure on his horse, Blue Rocket, bravely riding for the lead to try and turn the terrified herd. The next morning, the tragedy is discovered: Joe and his horse have fallen into a deep washout, the boy crushed to death.

Marty Robbins’ version, with its clear, emotive delivery and subtle backing, treats this tale with the reverence it deserves. It’s a song about a fleeting, innocent dream—the yearning of an orphan for belonging and a man’s job, and the brutal finality that so often waited on the rugged trail. For older listeners, it’s more than a song; it’s a window into the romanticized, yet often cruel, reality of the Old West. It reminds us of a time when courage was a daily necessity and a strong code of conduct governed those lonely lives. When Robbins’ voice rings out, particularly the final, tear-inducing lines, we don’t just hear music; we see the flickering campfire, feel the dust in the air, and mourn for a “little Texas stray” who finally found his calling, only to be taken far too soon. The song remains one of the Western Writers of America’s “Top 100 Western Songs of all time,” a quiet classic that keeps the memory of the working cowboy alive.