A solitary cry in the dusk of love’s retreat

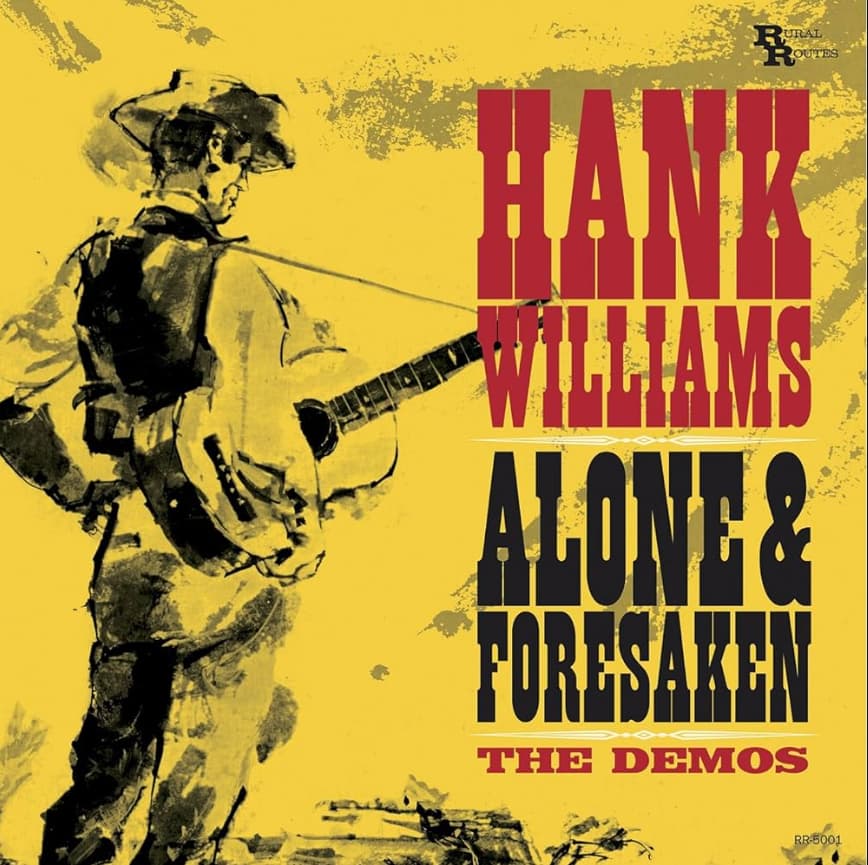

When Alone and Forsaken drifted into existence, it came not as a triumph but rather as a ghostly whisper—recorded by Hank Williams sometime between August 1948 and May 1949 during his live broadcasts at KWKH in Shreveport, Louisiana. The song did not chart in the conventional sense in his lifetime, and when it was finally released by MGM Records in July 1955 as the B-side to “A Teardrop on a Rose,” it was already posthumous, Williams having passed away at the dawn of 1953.

In that layered fact alone lies a kind of elegy: a song planted in the moment of its creator’s frailty, released into the world when his voice could no longer bring it forth in person.

In the hush of the recording—just Williams’s voice and his acoustic guitar—the mood clouds around you. Unlike the more raucous honky-tonk fare that made him a star, “Alone and Forsaken” slips into the realm of folk, of raw confession and skeletal emotion. Williams uses sparse instrumentation and a minor key—remarkably set in A-minor—to frame themes of desolation and heartbreak, a lonely figure left with nothing but his regret: “Alone and forsaken by fate and by man / Oh Lord, if you hear me, please hold to my hand, oh please understand.”

Here lies not the swagger of the country-chart hit, but the sad grandeur of a man stripped of everything: his love gone like “leaves now withered and gone,” the “meadows gold” of memory turned barren. It is this duality—of memory’s lush promise and present’s absolute emptiness—that gives the song its haunting power. Williams’s phrasing ‘half-spoken’ in the verses further emphasizes the thin line between song and confessional.

While the song did not achieve entry onto the major country charts in his lifetime (and detailed chart-peak data is absent or undocumented), its subsequent life has been rich: it was picked up in tribute albums, covered by artists ranging from Emmylou Harris and Mark Knopfler to Neko Case, and even found a cinematic place in the trailer for the television adaptation of The Last of Us in 2022.

The story behind “Alone and Forsaken” is as enigmatic as its tone. We know Williams recorded it in the shadowy environs of a radio studio, between 1948 and 1949—yet it remained unreleased until after his death. Some biographers suggest that the song reveals an emotional undercurrent in Williams’s life: his multiple loves, his struggles, and his enduring sense of abandonment. [Suy luận] The starkness of the arrangement suggests a man unguarded, stripped of friends and applause, bearing only his guitar and the hollow echo of lost affection.

In listening, one hears the bone-quiet moment when the stage lights have dimmed and the audience gone home, and the singer remains alone with his grief. The minor key creates a subtle shift from Williams’s usual major-key briskness; the absence of full band or backing vocals leaves the listener leaning in closer—feeling the breath, the pause, the ache. One may recall in other Williams songs the honky-tonk rhythm, the fiddle and steel guitar drive—but here, the world has collapsed inward.

Lyrically, the song unfolds as a journey from green pastures to lifeless fields. Past love is golden; present solitude is grey. The invocation of fate and man (“by fate and by man”) places the blame outside the self, but also inside the self—a recognition of one’s own role in the isolation. The plea to God, “Oh Lord…please hold to my hand”, turns the song toward an almost spiritual desolation. It is not simply that love is gone, but that the singer is severed from meaning, from connection, from humanity.

Its legacy, though quiet, is abiding. For older listeners who remember when records spun slowly and voices carried the weight of entire nights, “Alone and Forsaken” stands as a testament to the emotional depth country music could reach—not just its barrooms and heartbreaks, but its bare confession, its whisper into the darkness. Williams’s voice, recorded in a lobby or radio studio decades ago, still carries: a tremor, a memory, a life concluded yet still singing.

In hearing it, one is reminded that sometimes the truest music is not the triumphant anthem, but the solitary cry—echoing long after the applause has faded.