A defiant rhythm bearing the scars of confinement and the promise of redemption

When “I Got Stripes” was released in July 1959 by Johnny Cash, it entered the charts with an unmistakable edge, reaching a peak of No. 43 on the Billboard Hot 100. On the country side, it became one of his top‑10 entries that year, securing a place among the most remembered jailhouse narrations of the genre.

The moment the record begins, Cash’s trademark baritone stakes its claim: “On a Monday I was arrested… On a Tuesday they locked me in the jail…” The voice is unflinching, the rhythm driving, and the listener immediately understands that this is not a lament but a declaration — “I got stripes around my shoulders, and chains around my feet.” The simple structure and relentless delivery keep the story tight, yet the lines hang in the air long after the notation finishes.

Behind the track lies a historic lineage. The song’s authorship is credited to Johnny Cash and his friend DJ Charlie Williams, yet the composition draws directly from the folk‑blues classic “On a Monday” by Lead Belly, originally recorded in 1939. Cash and Williams adapted that narrative of incarceration, re‑cast it in the country style, and imbued it with the Man in Black’s unmistakable weight. Cash recorded “I Got Stripes” on March 12, 1959, for Columbia Records (catalogue 4‑41427) and paired it with “Five Feet High and Rising” on the flip side.

Lyrically and thematically, “I Got Stripes” functions on multiple levels. On the surface it is a prison song: the narrator goes through the days (“Monday… Tuesday… Wednesday… Thursday …”) and ends with the judge’s gavel and the chains. Yet beneath the surface, there is a reflection of guilt, consequence, identity, and redemption. The “stripes” could be literal prison stripes, but also metaphors for the visible scars that flag a life of missteps. The “chains around my feet” speak of constraint, but the act of singing them out becomes a kind of liberation. It transforms the song from one of captivity into one of voice reclaimed.

Musically, the track diverges from mournful prison‑ballad convention. Instead of a slow dirge, Cash chooses a brisk tempo, giving the record a swagger even while it speaks of confinement. The instrumentation is spare but effective—guitar, rhythm, bass—and the production allows the vocal to remain front and center. As one historian aptly summarizes, “a raucous prison tale,” not surrendered to sorrow but issuing from it.

For those who lived through the golden age of country radio, the song echoes like static from a dial tuned too fine. It captures the era of storytelling when a man with a guitar could transform time served into songs heard across radio waves. Cash’s voice carries the weight of experience, but also the possibility of redemption—not in a heavenly after‑life but here, in the chord progressions and the listener’s attention.

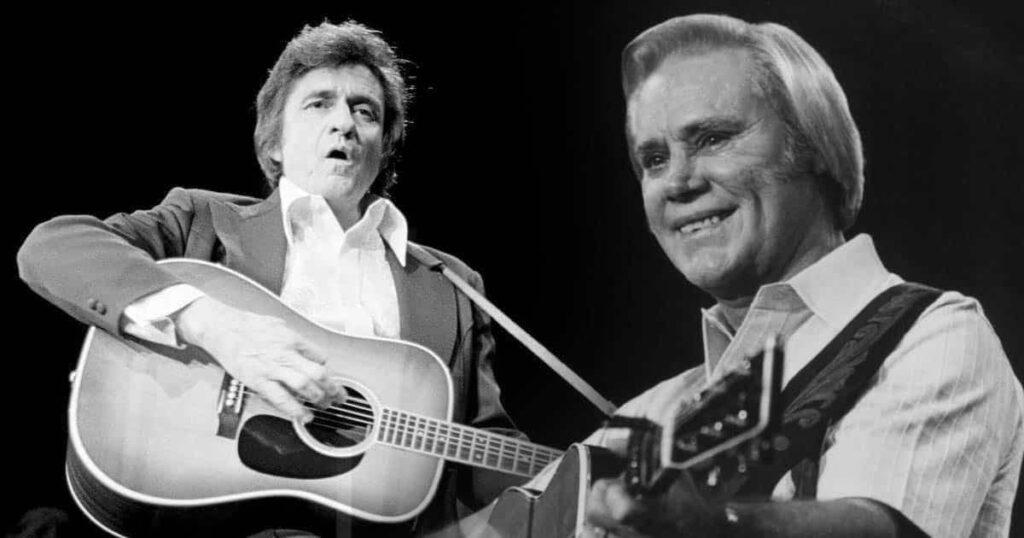

Although the version with George Jones, widely circulated in later years, is often cited, the original Cash solo recording remains the touchstone. In that lone voice singing of stripes and chains we find both the trap and the triumph. While chart positions only tell part of the story—the No. 43 peak and country Top‑10 placement—they do mark the song’s reach beyond mere novelty into the territory of enduring classic.

In its wake, “I Got Stripes” finds its place among Cash’s most vital recordings—not just because of chart numbers, but because of its honesty, its lineage, its transformation of the prison‑song tradition into something universal. The stripes, once symbols of punishment, become badges of survival once voiced. And the listener, leaning back and letting the record play, realizes that the door may be closed, but the song is open.