A Conversation Between Generations, Where Country Music Looks Back at Itself With Honesty and Respect

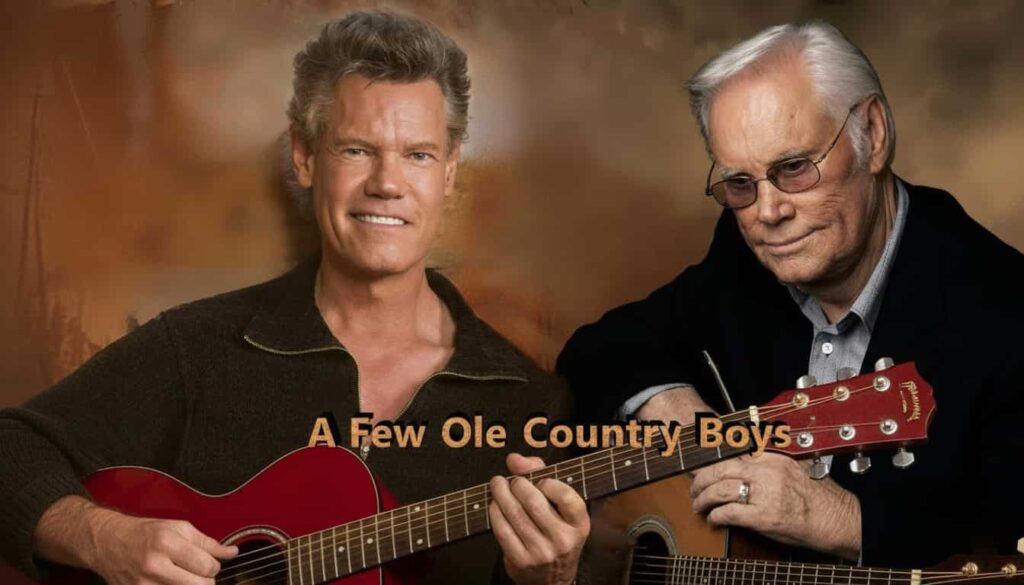

Released in November 1990, “A Few Ole Country Boys” arrived at a pivotal moment in country music history, when tradition and revival were not opposing forces but partners in dialogue. Issued as the lead single from Randy Travis’s duet album Heroes & Friends, the song reached No. 8 on the Billboard Hot Country Singles & Tracks chart and No. 4 on Canada’s RPM Country Tracks chart, a respectable showing that understated its deeper cultural significance. Written by Troy Seals and Mentor Williams, this was not merely a chart entry. It was a statement of lineage, gratitude, and continuity.

By 1990, Randy Travis was widely regarded as the standard bearer of the neotraditional country movement. His breakthrough album Storms of Life in 1986 had already sold over four million copies and reintroduced classic baritone vocals, emotional restraint, and honky tonk values to a genre drifting toward pop gloss. Travis was young, commercially dominant, and influential. George Jones, by contrast, represented the emotional bedrock of country music itself. Decades earlier, Jones had defined the art of heartbreak with songs that cut deep not through volume, but through vulnerability. When these two voices met on “A Few Ole Country Boys”, it felt less like a collaboration and more like a passing of wisdom.

The song unfolds as a reflective conversation between two men shaped by jukeboxes, neon lit bars, and nights that never quite ended on schedule. Its lyrics are deceptively simple. There is no grand metaphor, no melodrama. Instead, it speaks in the language of lived experience. These are men who have seen the cost of the road, who understand that music is not merely entertainment but survival. The phrase “a few ole country boys” becomes a quiet badge of honor, worn without nostalgia for its own sake, but with acceptance of what time leaves behind.

What makes the recording so powerful is the contrast in delivery. Randy Travis’s smooth, measured baritone carries reverence and restraint, while George Jones brings a weathered emotional authority that cannot be imitated. Jones does not sing the song so much as inhabit it. Every line carries decades of joy, regret, excess, and endurance. This was not acting. It was autobiography filtered through melody.

The importance of “A Few Ole Country Boys” extends beyond its original release. In 2007, the song gained renewed resonance during the George Jones And Friends 50th Anniversary Tribute Concert, recorded for PBS’s SOUNDSTAGE series and later released on DVD by New West Records. Hosted by Reba McEntire, the concert celebrated Jones’s half century legacy with performances by artists such as Emmylou Harris, Kris Kristofferson, Alan Jackson, Vince Gill, Kenny Chesney, and Martina McBride. In that context, the song felt prophetic. What had once been a duet between two men now echoed as a broader acknowledgment from an entire genre.

Thematically, the song stands as a meditation on belonging. It affirms that country music is not owned by trends, eras, or commercial cycles, but by stories passed from one voice to another. The “heroes and friends” concept behind Randy Travis’s album was not a marketing device. It was a declaration of artistic debt. Few songs on the album express that debt as clearly or as humbly as this one.

Today, “A Few Ole Country Boys” remains a quiet cornerstone of modern traditional country. It does not shout its importance. It waits patiently, like the records that once spun late at night when the world slowed down enough to listen. In its gentle honesty, the song reminds us that country music endures not because it changes, but because it remembers.