A Gentle Voice That Turned Christmas Into a Feeling

There are countless versions of “Jingle Bells” — playful, brassy, full of cheer — but only one that glides in softly, like falling snow at twilight. When Jim Reeves recorded his version of “Jingle Bells” for his 1963 holiday album Twelve Songs of Christmas, he transformed one of the world’s most familiar carols into something entirely new: a warm, velvet-smooth reflection of Christmas itself. Instead of the lively sleigh ride we all expect, Reeves offered a slower, richer moment — one that sounded like home, memory, and comfort woven together.

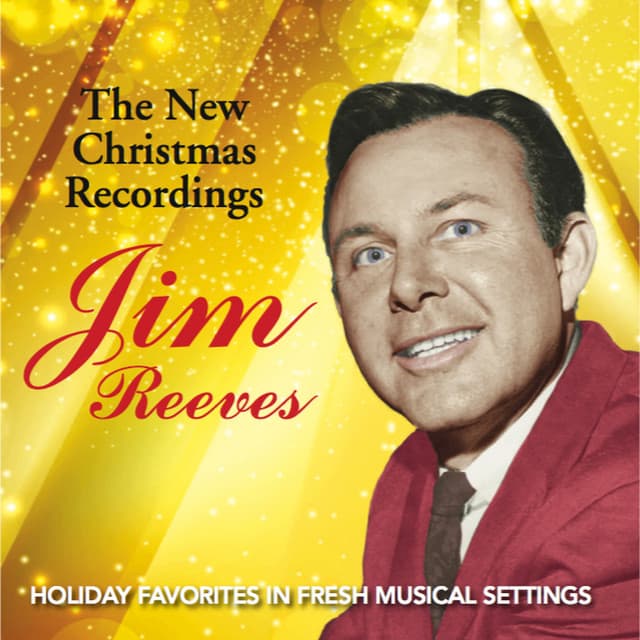

Released in October 1963 by RCA Victor, Twelve Songs of Christmas charted modestly upon release, but in the decades that followed, it became a perennial favorite, particularly among listeners who longed for gentleness amid the glitter and noise of the season. Reeves’ “Jingle Bells” never appeared on the Billboard Hot 100 — it wasn’t meant to. It wasn’t chasing trends or commercial success. It was meant to linger — in kitchens lit by soft yellow bulbs, in late-night radio broadcasts where his voice felt like a friend keeping you company.

Jim Reeves, known affectionately as “Gentleman Jim,” had already established himself as one of country music’s most distinctive voices before turning to Christmas music. With hits like “He’ll Have to Go”, “Welcome to My World,” and “Four Walls,” Reeves brought to popular music something rare: restraint. His singing wasn’t loud or showy; it was intimate, deeply felt. In “Jingle Bells,” that very quality turns a jovial tune into a nostalgic reverie. The sleigh ride becomes a memory — not of laughter and noise, but of togetherness, of being safe and warm as the snow falls outside.

The arrangement, guided by Chet Atkins’ production touch, captures that atmosphere perfectly. Soft orchestration, gentle strings, and a hint of background choir frame Reeves’ low, resonant baritone. He doesn’t rush the rhythm; he lets each word breathe. Even familiar phrases like “Oh, what fun it is to ride” sound less like excitement and more like gratitude. Listening to it feels like watching Christmas through frosted windows — calm, reflective, tender.

What makes Reeves’ rendition remarkable is not the melody, but the mood. His “Jingle Bells” reminds us that Christmas is not only about celebration; it’s about remembering. About family members who once filled the room with laughter, about long drives through snowy roads, about voices that now exist only in recollection. It carries a quiet emotional truth: joy and sadness often sit side by side during the holidays, and that mixture is what makes them meaningful.

In many ways, Reeves’ approach anticipated what later generations would call “countrypolitan” — a sound that blurred the boundaries between country, pop, and easy listening. But beyond genre, what makes this performance endure is the sincerity at its core. Reeves wasn’t just singing a Christmas song; he was offering it — as one might offer a cup of coffee to an old friend on a cold evening.

After his tragic passing in a plane crash in 1964, just months after the album’s release, songs like this took on a new, almost spiritual quality. His Christmas recordings, once merely comforting, became deeply personal for those who loved him — a way to keep his presence alive during a season defined by memory and reunion. Each December, when that familiar voice returns to the airwaves, it feels as if he never truly left.

“Jingle Bells”, in the hands of most singers, is an invitation to join the fun. In Jim Reeves’ hands, it becomes something else entirely: a moment to pause, to breathe, to remember what joy once felt like — and still can. It is a song not just for celebration, but for reflection. A song for those who have lived enough Christmases to know that the quietest ones are often the most beautiful.

Listening to his version now is like opening an old photograph album — one filled with faces you can still see, laughter you can almost hear, and a warmth that time cannot erase. That’s the magic of Jim Reeves — the man who could take a song everyone knew, and make it feel, once again, like the very first snowfall.