Marty Robbins – Aloha Oe (Farewell To Thee): The Quiet Heart of the Cowboy Crooner, Bridging the Arizona Desert to the Shores of Hawaii

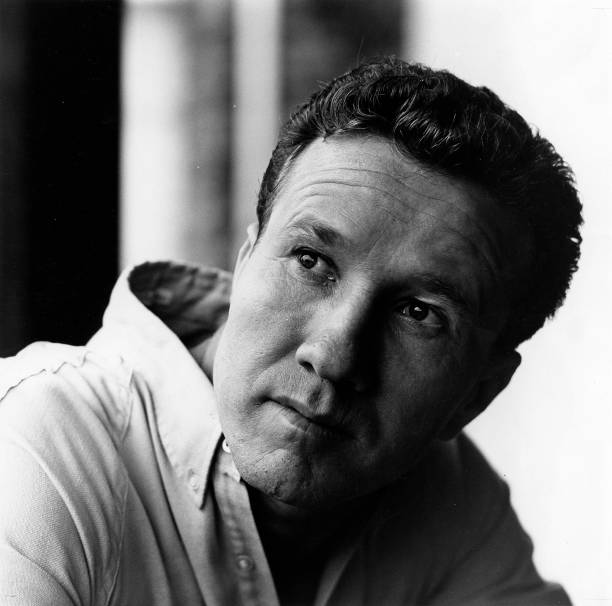

There are few voices in the history of American music as versatile, yet as consistently comforting, as that of Marty Robbins. He was the cowboy of the gunfighter ballads, the rocker of “White Sport Coat,” and the crooner of heartbreak, yet for those of us who appreciate the breadth of his artistry, he was also a passionate devotee of Hawaiian music. His recording of “Aloha Oe (Farewell To Thee)” is a beautiful, deeply personal glimpse into this often-overlooked facet of his career, a gentle, steel-guitar-laced embrace that serves as a quiet contrast to his dramatic Western sagas.

For readers of a certain age, who remember an America still captivated by the exotic sounds of the Islands, this song holds a special, nostalgic place. Robbins’ connection to Hawaiian music was genuine; he developed a taste for it while serving in the U.S. Navy during World War II, a time when the peaceful, lilting melodies provided a balm for the soul. This song wasn’t a one-off novelty; Marty Robbins released entire albums dedicated to the genre, like Song of the Islands and Hawaii’s Calling Me. His version of “Aloha Oe” was recorded early in his career and was later included on various compilations, reflecting its enduring popularity among his fans, a testament to his smooth, warm baritone being perfectly suited to the gentle lilt of the music.

The song itself is a piece of living history. “Aloha Oe” (which translates to “Farewell to Thee”) was written around 1878 by Queen Liliʻuokalani, who was then Princess of the Hawaiian Kingdom. The story goes that she was inspired by a tender farewell embrace between Colonel James Harbottle Boyd and a young woman during a horseback trip. The Queen composed the song as an expression of love, longing, and final parting. It has since become the most famous song to ever come out of Hawaii—a cultural icon symbolizing the Islands’ spirit, and often, their lost sovereignty. The famous chorus, “Aloha ʻoe, aloha ʻoe, E ke onaona noho i ka lipo, One fond embrace, a hoʻi aʻe au, Until we meet again,” is more than just a sweet goodbye; it’s a promise of return, a deep, poetic yearning for someone cherished who must leave.

What makes Marty Robbins’ recording so memorable, particularly for a country audience, is his subtle, respectful Nashville arrangement. Instead of the typical grand orchestra, he used a signature element of both Country and Hawaiian music: the steel guitar. With masterful players like Jerry Byrd or Jim Farmer often contributing, the steel guitar’s liquid, crying sound provides the emotional core, mirroring the Hawaiian lilt while maintaining a touch of the melancholy that his Country fans adored. This blend allowed the song to cross over, not on a pop chart (it was generally not released as a contemporary single, and thus does not have a formal chart history like “El Paso”), but into the shared heart of the American public.

Listening to Marty Robbins sing this song is a comforting experience, like watching an old home movie. You hear a man who was unafraid to pour his whole heart into a melody, whether he was singing about a dramatic shootout in El Paso or the soft, sweet sorrow of a Hawaiian goodbye. It evokes a simpler time, when a beautiful melody was enough, and a song could carry the warmth of an island breeze across the mainland. It reminds us that in the hands of a master like Marty Robbins, a farewell isn’t just an ending; it is a profound, heartfelt promise of “Until we meet again.”