Marty Robbins’ “Streets of Laredo” (1960): The Immortal Lament of the Dying Cowboy

There are songs that pass through generations, evolving like an old river carving a new path, yet always carrying the same emotional weight. “Streets of Laredo” is one such song, a cornerstone of the Western ballad tradition, and the version recorded by Marty Robbins in 1960 stands as perhaps the definitive, most mournful interpretation. This track, included on his seminal album, More Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs, which followed his hugely successful 1959 masterpiece, Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs, cemented Robbins’ reputation as the genre’s most gifted storyteller and musical dramatist.

Unlike some of his original compositions, such as the chart-topping “El Paso” which had crossed over to become a Number 1 hit on both the Country and Pop charts that same year, “Streets of Laredo” was a traditional folk song. As such, it did not have a conventional chart run as a single in 1960, but its presence on the hugely popular More Gunfighter Ballads album ensured it received constant radio airplay and became instantly recognizable to a vast, loyal audience. It is, without question, one of the most recorded and reinterpreted songs in the Anglo-American folk canon.

The fascinating backstory of “Streets of Laredo” stretches back across continents and centuries. It is an American adaptation of an older British folk song known as “The Unfortunate Rake” (or “The Unfortunate Lad”), which dates back to the 17th or 18th century. In its oldest forms, the protagonist was often a soldier or sailor who was “cut down in his prime,” sometimes lamenting an early death due to venereal disease. When this narrative traveled to the American West, it was naturally molded by the frontier experience. The dying man was transformed into a young cowboy or ranger, and the English city was replaced by the Texas border town of Laredo. The moralizing core, however, remained: a regretful lament for a life wasted on drinking, gambling, and loose living.

The meaning of the song, particularly as delivered by Marty Robbins, is a profound meditation on mortality, repentance, and the fragility of life on the frontier. The song is a dialogue: a passing cowboy spies another wrapped in linen, “cold as the clay,” who delivers his final, tragic monologue. “I see by your outfit that you are a cowboy,” the dying man says, recognizing a shared path. He then offers his last wishes: “Oh, beat the drum slowly and play the fife lowly / Play the dead march as you carry me along.” These final requests—for a slow march, low music, and a burial in the little green valley—are heart-wrenching in their simplicity, a young man stripped of all his worldly swagger, asking only for a moment of solemn dignity.

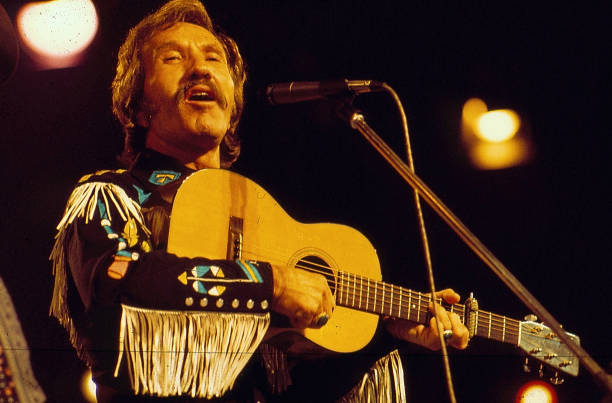

Robbins’ rendition is a masterclass in vocal restraint and emotional depth. He doesn’t need to shout the sorrow; his gentle, measured tone is the sorrow. His performance on the More Gunfighter Ballads album is often less dramatic than some of his originals, allowing the sheer weight of the traditional lyric and the simple arrangement—often just his guitar and a light touch of accompaniment—to carry the emotional burden. For older listeners who remember a time when songs didn’t need loud theatrics to convey deep feeling, this version is perfect. It speaks to the quiet wisdom that comes with age, acknowledging that even in a rough-and-tumble life, a man hopes for a decent, quiet end.

Listening to Marty Robbins sing “Streets of Laredo” is not just listening to an old record; it is sitting on a front porch with a ghost of the past, hearing a truth whispered across the decades. It’s a powerful reminder of where we come from and the timeless lessons about living a good life, a song that feels less like entertainment and more like shared history.