Loretta Lynn’s landmark song is a powerful and candid plea for sobriety and respect in a marriage.

A Sobering Truth in a Country Melody

Ah, to be transported back to 1967. A year of immense social change, of blossoming youth movements and the Vietnam War raging, yet on the airwaves, a voice of raw, unvarnished truth was cutting through the noise. It was the voice of Loretta Lynn, a woman who sang not of fairytales or idealized romance, but of the hardscrabble reality of rural life. Her song, “Don’t Come Home A-Drinkin’ (With Lovin’ on Your Mind),” wasn’t just another tune; it was a defiant anthem that spoke to the silent suffering of countless women across America. It’s a song that, even all these years later, retains its powerful sting and its profound, heartbreaking honesty.

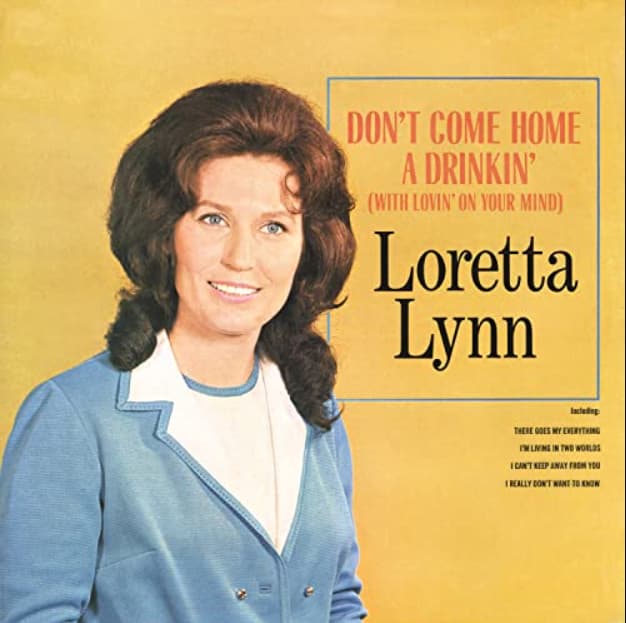

This was a song that didn’t just top the charts; it made a statement. Released in February 1967 as the lead single from her album of the same name, it was an immediate sensation. It wasn’t long before it climbed to the pinnacle of the Billboard Hot Country Singles chart, a position it held for two weeks in April 1967. This wasn’t just a hit for Loretta; it was a landmark moment for female country singers, solidifying her as a force to be reckoned with. It was the first song by a female country artist to hit No. 1 that was also written by the artist herself. It was a testament to her unique voice and her unflinching commitment to writing and singing about the truths of her own life and the lives of the women around her.

The story behind this song is as real and as poignant as the lyrics themselves. Loretta Lynn penned it with her sister, Peggy Sue, and it was inspired by the very real struggles she and her husband, Oliver “Doolittle” Lynn, faced. It was a direct address to Doolittle, a man who, by all accounts, was known to enjoy a drink or two. The song isn’t an attack, but a plea. It’s a weary request for a man to choose his wife and his family over the bottle. The lyrics are simple yet devastatingly effective: “Well, you thought I was a fool to be foolin’ with you, / So you’d go out and get tanked up and tell me what you’d do.” It’s a narrative of broken promises and unfulfilled desires, a woman’s frustration and sadness laid bare for all to hear. The “lovin’ on your mind” is not a romantic overture but a weary resignation, a recognition that physical intimacy is not a salve for a deeper emotional and relational wound.

For many women of that era, particularly in the South and rural areas, this song was their voice. It spoke of a dynamic that was all too common—a man who worked hard, played hard, and then came home expecting a wife who was ready and waiting, regardless of his state. The song’s genius lies in its refusal to be preachy or judgmental. Instead, it’s a song of quiet strength, a woman standing her ground and demanding to be seen not just as a domestic servant, but as a human being with her own needs and feelings. Loretta Lynn wasn’t just a singer; she was a chronicler of the times, a poet of the working-class American woman. She gave a voice to the voiceless, validating their experiences and their pain in a way that had rarely been done before in mainstream music. This is the heart of her legacy. It is in songs like “Don’t Come Home A-Drinkin’,” a song that remains as relevant today as it was in 1967. It’s a reminder of a time when music didn’t just entertain; it spoke a hard truth.