The Ash and The Echo: How Marty Robbins Made a Wildfire His Most Chilling Ballad

For those of us who came of age with the sound of a six-shooter and a mournful acoustic guitar defining our concept of the American West, the name Marty Robbins is sacrosanct. He was not merely a country singer; he was the foremost musical chronicler of the frontier, a magnificent storyteller whose ability to create high-stakes drama in song remains unmatched. While his fame rests on the timeless, mythic power of tracks like “El Paso” and “Big Iron,” to truly appreciate his genius is to explore the wider tapestry of his Western works, particularly the masterful atmospheric pieces like “Prairie Fire.” This song trades the human-versus-human conflict of the gunfighter genre for a stark, primal struggle against nature, and in doing tissue, creates one of his most chillingly realistic ballads.

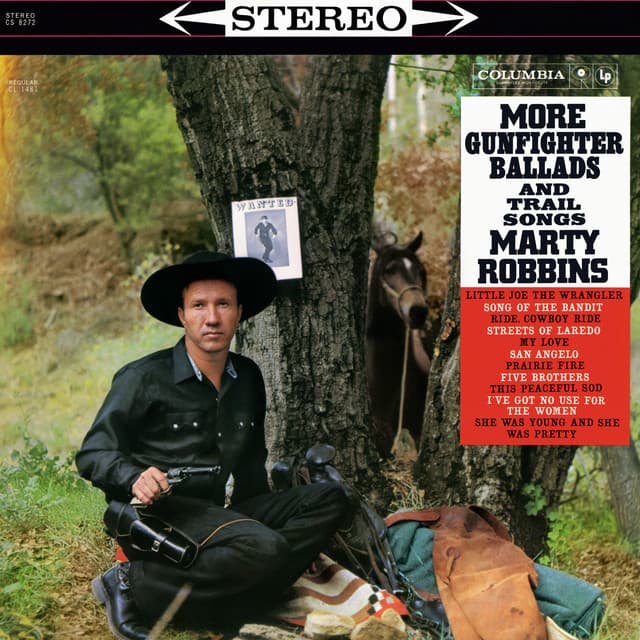

Crucially, the song “Prairie Fire” was not featured on the first, most famous volume of his Western recordings. Instead, it was included on the sequel album, More Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs, released in July 1960. This album followed the massive success of the 1959 original and confirmed Robbins’s deep commitment to the genre. As an album track and not a promotional single, “Prairie Fire” did not register on the major contemporary charts, such as the Billboard Hot 100 or the Hot Country Singles chart. The song, written by Joe Babcock, is a testament to the fact that Robbins was recording for artistic depth and thematic completeness, not just chasing commercial airplay. The track is notable for featuring the superb guitar work of Grady Martin, whose crisp, urgent playing was integral to establishing the authentic sound of Robbins’s Western catalogue. The meaning of “Prairie Fire” is delivered with the devastating clarity of a news dispatch from the field.

It is a first-person narrative, sung from the perspective of one of a crew of cowboys—thirty men, driving a herd of cattle eastward across Nebraska—who suddenly find themselves in a race against an overwhelming inferno. The story arc is breathtakingly rapid: a distant dark cloud on the horizon, the air growing hot and dry, the unmistakable, terrifying roar that “topped the Devil’s choir,” and then the visible flame “a-lickin’ at the sky.” The song vividly captures the sudden, existential panic of the moment, realizing that the only hope lies in reaching the distant river flat. Robbins’s performance here is simply breathtaking. His vocal is pitched with a strained intensity that perfectly conveys the rider’s exhaustion and dread—the sound of a man pushing himself and his horse to the absolute limit. The relentless pace of the music, driven by the rhythmic, galloping percussion, never lets up, effectively mimicking the frantic, doomed flight of the herd. The genius of the song, and what makes it so resonant for us older listeners, is its unflinching, tragic conclusion: the cowboy fails.

He loses the race, and the final verses are a grim, somber report from the blackened aftermath, revealing that of the “thirty men” and the entire herd, only the narrator survives to tell the tale. It’s a powerful, sobering reminder of the merciless scale of the natural world, and it serves as a powerful contrast to the often romanticized duels, offering a deeper, more profound form of peril that was central to the life of the real frontier. This forgotten track is a masterpiece of storytelling that anchors the More Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs album with its somber, reflective conclusion, securing its place as an essential piece of Marty Robbins‘s enduring legacy.