The Ghost in the Machine: When Glam Rock’s Heaviest Band Went Abstract

If you were a fan of Sweet in the 1970s, you knew them as the architects of stadium-sized glam-rock anthems, the band with the outrageous clothes and the powerhouse vocal harmonies. You expected the raw thrust of “Block Buster!” or the infectious energy of “Ballroom Blitz.” But then you flipped over one of their albums, sat back in your armchair, and were confronted with the haunting, beautiful, and utterly unexpected experience that is “Air On ‘A’ Tape Loop.”

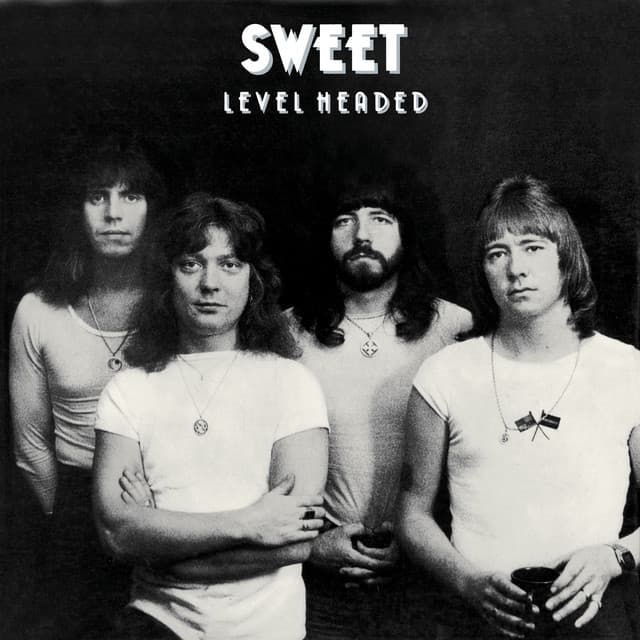

This remarkable track is an instrumental, experimental piece, and it perfectly encapsulates the internal tug-of-war that defined the career of Brian Connolly, Steve Priest, Andy Scott, and Mick Tucker. It was not released as a single, and therefore, it has no historical chart position to speak of. It exists not as a pop hit, but as an album track—a deep cut that rewards the devoted listener. The most commonly recognized version of this song appears as the second part of a two-part composition, usually paired with “Anthem No. II,” on their 1978 album, Level Headed.

The story behind “Air On ‘A’ Tape Loop” is the story of Sweet’s gradual, yet determined, rebellion against their pigeonhole. By 1978, the band had already fully broken free from the control of their hit-making producers, Nicky Chinn and Mike Chapman, and were deep into exploring more complex, layered, and artistic sounds. The album Level Headed itself was a major departure, leaning heavily into progressive rock, symphonic arrangements, and keyboard textures—a far cry from the guitar-driven hard rock of Desolation Boulevard or Give Us a Wink.

“Air On ‘A’ Tape Loop” is a stunning piece of sonic architecture built around the literal use of tape loops, a technique borrowed from the avant-garde musique concrète of the 1950s and 60s. The song’s title is a wry, knowing nod to classical music, referencing J.S. Bach’s “Air On A G String,” but replacing the elegant string work with a mechanical, cyclical repetition of sound. It’s a hypnotic swirl of atmospheric synths, echoes, and distorted, almost dream-like fragments that drift in and out of focus.

The meaning here is less about a traditional narrative and more about mood, texture, and the exploration of sound as an entity. It suggests a certain introspection, an artistic desire to strip away the glamour and the hits to reveal the serious, ambitious musicians underneath. This wasn’t the sound of Sweet selling records; it was the sound of them making a statement—a highly intelligent, abstract piece of work that demanded respect. It was their quiet protest, tucked away on an album that confused many at the time but which, decades later, sounds like an incredibly brave and forward-thinking move.

When you drop the needle on this track now, the memories it evokes are not of glitter and Top of the Pops, but of solitary hours spent in a darkened room, headphones on, trying to make sense of the world—and this new, strange, beautiful sound. It’s a reminder that true rock and roll heroes are never static, always pushing against the expectations of the crowd to follow the dictates of their own creative muse. It’s a powerful, atmospheric moment that allows us to reflect not just on Sweet’s journey, but on the complexity of music itself.